Carter's Grove Architectural Report, Block 50 Building 3Originally entitled: "Landscape Features of Carter's Grove"

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library Research Report Series - 1625

Colonial Williamsburg Foundation Library

Williamsburg, Virginia

1990

To: Edward A. Chappell

From: George H. Yetter

Subject: Landscape Features at Carter's Grove Block 50, Building 3

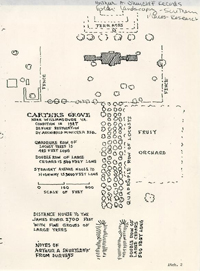

The present boxwood and other garden schemes at Carter's Grove are the work of Arthur A. Shurcliff and have been in place since ca. 1929. They evolved from study of extant Tidewater gardens and use of existing landscape features already on the site. An 1874 plat records a straight, central, tree-lined entrance road from the present Route 60.1 Sydney Smith's plat of 1907 shows the same landside entrance drive which is labelled "old road to mansion house."2 The large locust trees--moribund, dead, and some recently removed--were a feature at the sides of this lane approaching the house, as shown in early 20th century photographs (See Attachment 1). Shurcliff's own plan of the house and grounds (Attachment 2), done in 1927 before renovations by the McCreas, notes a 425 foot long quadruple row of locust trees, and a 500 foot long double row of large cedars.

A few facts concerning Shurcliff's career and accomplishments are in order. Taking his degrees at Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Harvard, he worked first with the form of Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr. in Brookline, Massachusetts. He helped Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. found Harvard's School of Landscape Architecture and, by 1905, established his own office in Boston. Work during this period, in consultation with such leading firms as McKim, Mead, and White; Peabody and Sterns; and Ralph Adams Cram; included planning for Amherst, Brown, Johns Hopkins, and Harvard universities. Private garden commissions were carried out from Canada to Florida and as far west as California. Several years ago, following devastating storms, Shurcliff's plans for Amherst were reimplemented.2A He was president of the American Society of Landscape Architects for two terms. Later work included Boston Common and Old Sturbridge Village. Frequently noted and often discussed in published studies of landscape architecture, his talents were recently under study at CW by Hope 2 Cushing, a doctoral student from Boston University, who came especially to see the unique collection of original sketches in the Architectural Drawing Archives.

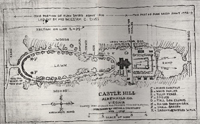

Illustrative of the lessons mentioned by Shurcliff as being learned on visits to Tidewater plantations, and pertinent to the work in question, is the following passage among his 1929 letters to the owner of Carter's Grove, his client Archibald McCrea. "Another interesting fact is the universal symmetrical layout and the curious disposition of trees in such layouts of radically different kinds. The uniform use of one tree even in a single row seems to be father the exception, just as at Carter's Grove in the row on the south side of your house. Your large grove of symmetrically arranged Locust trees is apparently unique."3 The same letter appears to draw a precedent for what resulted from a visit to Castle Hill in Albemarle County, where the original owners "have not hesitated to use Box very freely near the entrance, more or less as you and I have discussed for Carter's Grove." Shurcliff's measured plan of Castle Hill is provided in Attachment 3.

Another letter gives further insight to sources of precedent for what resulted at Carter's Grove. It concerns the double roadway at the entrance, which Shurcliff notes is an unusual feature in southern places. He calls attention, however, to the "extraordinarily attractive double road scheme at Castle Hill . . . . This very long double approach probably dates from about 1800 and is exceedingly delightful. If these lateral roadways were straight they would be very much like the schemes we devised for Carter's Grove. I have no doubt you are right that the ancient approach to Carter's Grove was probably straight down through the Locusts. Nevertheless the double roadway scheme we discussed was exceedingly charming, and in these days of motor vehicles it had much to recommend it. The approach to Carter's Grove is so exceedingly long that this departure from an axial line at the last moment could be regarded as a reasonable development of the old local turnaround [which it appears the property had in earlier periods] and would give a distinguishing feature to Carter's Grove which all the other places lacked."4 Also, Shurcliff compares this feature to the approach drive at Tuckahoe and says that there "the present approach swings off to one side at about the same distance from the house that we are proposing to swing off at Carter's Grove. The family say this was done to get rid of motors immediately in front of the house.5

Original Shurcliff sketches for landscape plans at Carter's Grove provide an understanding of the present scheme's development. The earliest is a rough sketch showing "condition in 1927 before restoration by Archibald M. McCrea, Esq."6 Another 3 measured plan of extant conditions drawn in September, 1928 records the axial dirt drive centered on the landside entrance. Notations identify a laterial "line of 18"-24" locusts."7 This measurement refers to trunk diameter at about four feet above ground, and indicates an age of about 50 to 60 years.

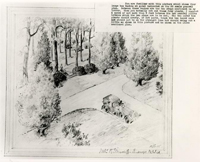

The first study for landscape renovations, dated September, 1928, delineates an elaborate system of box gardens, arbors, and maze, all located west of the mansion, with the landside entrance road divided about 750 feet from the house and forming an elongated oval. Within this, an axial vista is retained along a central walk, bordered by low shrubs and rows of trees aligned with the extant cedar lane leading from Route 60.8 Another scheme for the vicinity of the house, drawn in the late fall of 1928 and labelled "Plan 1,"9 shows a layout similar to what ultimately evolved (See Attachment 4). Within the oval immediately in front of the house is an irregular pattern of existing trees along each side of a central flag-stone walk. Underneath these trees and along the walk is an "irregular thicket of evergreen planting including leucothoe, holly, ilex, andromeda, magnolias, and laurel arranged in scattered formation to look like old overgrown planting of great age."10 Evidently, boxwood were not initially considered for this location.

The final, executed landscape layout incorporated the remains of the quadruple line of symmetrically planted locust trees set out in the latter quarter of the 19th century. Shurcliff's "Measured Plan of Carter's Grove" (1928) and photographs taken in 1907 substantiate this feature. Photographs from ca. 1930 indicate that the box located at the corners of the main house's north facade (removed in December, 1983), and those across the drive on each side of the entrance walk, were features carried out under Shurcliff's supervision. Also, these particular bushes appear in his proposed sketches for landscape development (See Attachments 5-7).

The axis of the original, single-lane, entrance road was preserved in the vista created by Shurcliff when he placed box along the sides of a new central walk leading through the oval from the main north door. The various schemes grew progressively simpler and more naturalistic before implementation. The labyrinthine maze and variously shaped box parterres--horseshoe, diamond, oval, round, rectangular, square, and bisecting path plans based on the crosses of St. Andrew and St. George--were deleted. The formal entrance forecourt and elaborate boxwood parterre design, reminiscent of the English "Union Jack" and located near the office, were also dropped.

The McCrea era at Carter's Grove is a significant phenomenon in itself. Charles B. Hosmer, in his Presence of the Past, describes the first two decades of the 20th century, 4 during which a number of wealthy Americans bought old mansions and "restored" them with the purpose of living and entertaining on a lavish scale. "Dormer windows suddenly appeared where rooftops had been plain; servants' quarters grew out of the gill sides of buildings; partitions fell to make larger rooms ...."11 This was precisely the program followed by the McCreas's supervising renovation architect, Duncan Lee, in his metamorphosis of Carter's Grove into an elegant backdrop for the entertaining and lifestyle which were desired.

That such a concerted effort between client, architect, and landscape planner was the case at Carter's Grove is proven by Shurcliff's prospective sketches provided in Attachments 8-11. Proof that Westover was the principal model is clearly reflected in the clairvoyee fence, incorporating pedestals topped by birds alighting on globes, enclosing a central landside forecourt. In a notation by Lee, on comparative floor plans of Westover and Carter's Grove sent to Mrs. McCrea, he says: "You have often asked me about the sizes and . . . can see that everything is in favor of the 'Grove.'"12 The pleasant rapport existing throughout their mutual efforts was attested by Shurcliff in a letter to McCrea. He reminds him that: ". . . of course you will not forget my interest in Carter's Grove and the delight I have always hid in working out problems with you, Mrs. McCrea and Mr. Lee."13

The successful result of these mutual efforts was termed by diplomat-philanthropist Charles Francis Adams as "the most beautiful house in America."14 Concerning the landscape work, architectural historian and former Foundation architect, Thomas T. Waterman, in his classic The Mansions of Virginia, said: " …in recent years a fine garden and approach, which provides a sympathetic setting for the great house, have been developed."15 Recently, a Foundation consultant, Gus Hamblett, referred to the McCrea's "project of enormous scope which, under the direction of Richmond architect Duncan Lee and landscape architect, Arthur Shurcliff of Boston, transformed the mansion-house complex and the remains of its environs and aproach, into one of the major American estates of the 1930's."16 A vital portion of the total ambiance, the gardens are an integral part of what Carlisle Humelsine's guidelines, set forth in "Development of Master Plan for Carter's Grove," are referring to when he states: "The mansion itself will undergo no reduction in architecture or any other feature that reflects its gradual evolution as a great country house." 17

Further, Shurcliff's original garden design--particularly the layout of the landside entrance oval--is representative of the most current, innovative, and influential landscape principles of its time, as put forward by Gertrude Jekyll in England. When acreages surrounding country estates grew smaller, efforts were made to stop the visual encroachment of 20th century 5 industry and technology. Sweeping, open vistas were an extravagance of the past and usually--as at Carter's Grove--former vistas required shielding to obscure and lessen the detrimental effect of heavily travelled highways and urban growth. Even today, the tranquil country scene from the Carter's Grove landside entrance step is broken by bright flashes and accelerated movement along Route 60 in the distance. I understand that this road is scheduled for future widening into a four lane highway. That the romantic, naturalistic pattern was what Shurcliff had in mind for the site is borne out by his chart, "Chronological Outline of English and Virginia 'Place' Layouts." It is undated but was probably drawn up around 1930. In it he tabulates the original work at Carter's Grove as taking place in 1751 under the influence of the romantic revival. Further notations say: "Classic formality overthrown--rise of the English school of landscape gardening."18

To remove or diminish this necessary visual barrier which is just now achieving its intended goal--"to look like old overgrown planting of great age"19--calls to mind an experience of Shurcliff, himself. Describing a Gloucester County trip to locate boxwood for use in restored gardens, he realized the unfortunate consequences for the various sites. "The end of the places comes at the very time when they have reached surpassing beauty . . . the gardens, the house, and the great trees have at last filled out the plan which the owners and the builders have agreed upon a century or two ago when the sapling trees were planted, when the little springs of box were set out."20 Interestingly, he continues: "I began to see the Williamsburg work in this light too for the first time. It is something quite different from making a collection of antiques,--buildings, old furnishings, gardens, old trees, old associations. It is an infinitely greater thing to save a whole design which was planned for but never seen in its maturity by the planners. This whole design is a work of art and not a collection of single things like museum specimens. Of course, this viewpoint is not new to you and Mrs. McCrea or to Dr. Goodwin." 21

An idea of Shurcliff's preservation philosophy can be gained from his article, "The 'Skinning' of Ancient Virginia Houses." Discussing the association which plants may have with paths and doorways of old homes, and the perfected composition which only the maturity of time can bring, he asks: "What of the trees in rows which flanked the ancient front yard and the door-yard? The great age of the Cedars, Oaks, Elms and the flowering trees marked more than the passing of years since the original saplings were placed in accordance with a great general plan of which the house was only a part. The age of the trees marks the maturity of the plan and justifies the skill and the 6 vision of the ancient owner and the designer who planned the whole group of buildings and grounds with an eye to the ultimate picture. Not until long after these men died in their old age did the whole picture of the house mellowed by time, the garden grown to prime, and the trees in maturity, began to appear. Then all of a sudden when the full beauty began to reign indoors and in the garden and in the front yard and the door-yard, along came the 'skinner.' He runs ahead of old Father Time with a reaping hook more potent for instant ruin than the slow swinging scythe."22

A partner in the architectural firm which originally restored CW, William G. Perry, who worked closely with Shurcliff and termed him "indispensable,"23 also tellingly identified him as a "poet."24 Certainly, we can recognize this romantic quality in his philosophic approach to preservation, and realize that his poetic nature must have expressed itself in the work at Carter's Grove.

A comment sometimes heard concerns the size of the tree box. Enhanced insight into Shurcliff's own philosophic and aesthetic reasoning about the use of boxwood in the landscape appears in an early Foundation report. Following his extended study of early gardens in Virginia, he notes the generous use of box which is often the only extant remnant of original landscape planting. In replanting the Williamsburg places," he continues, "much use should be made of box even to the extent of allowing it to dominate the parterres and bed traceries of which it once formed only a part. Such domination is wholly justifiable as it would recall at once the old Southern places as they exist today in gardens where the box has overshadowed the flowers to which it was once a marginal frame."25 He refers, also, to an English parallel at Haddon Hall "where the corners of the old flower garden are marked with yew trees of great diameter and of a height above the Hall itself. These yews were planted to give an accent effect at the bed corners. The height was to be two or three feet and was to be controlled by clipping. As time went on the clipping was neglected and the trees grew so large that they overshadowed and destroyed the garden design. Today these trees are the great sight of the Haddon terraces . . .[and] they are more significant of that period than any new work."26 This dialogue concerning overgrown shrubs appears to have parallels with the tree box at Carter's Grove.

Recently, the idea was advanced that plantings are comparable to a line on a graph—that they reach maturity or crest and then decline.26 Consideration should be given to the great gardens of Italy--Boboli, Borghese, Villa d'Este--which, 7 through greatly extended maturity, have gained a beauty unimagined by their original planners. Bearing out this often important effect of time on garden pattern, the present Duchess of Devonshire, speaking of the romantic, naturalistic landscaping changes at Chatsworth by the consummate, 18th century, English landscape architect "Capability" Brown, observes: "I never cease to marvel at the imagination of his grand designs for large spaces, for the trees took a hundred and fifty to two hundred years to realize the effect he wished to make. Our parents' generation and our own have had the luck to live at the right time to see them at their best."28 A romantic work needs to be viewed in that light. There is an aura or evocative spirit that cannot be described on paper, but only experienced in the work itself. One of Webster's definitions for the term "romantic" is characterized by picturesque strangeness or variety."29 These qualities, and their action on the visitor's imagination, are palpably felt at Carter's Grove and add an important dimension to the overall experience there.

At this point, the closeness, mutual pooling of knowledge, and purposes that were shared between the founders of CW and the McCreas are worth remembering. They held similar credos concerning the reasons for their respective efforts. Mrs. McCrea's observation to a group involved with the restoration of Stratford Hall that: " . . . the future is built upon the experience of the past,"30 echoes CW's own Ruskinian motto: "That the future may learn from the past." This shared spirit and dedication was inculcated in the works at Carter's Grove, which represent their own era in as important a way as parts of the Historic Area picture an earlier period. Certainly, the Carter's Grove boxwood--some among the largest specimens on Foundation properties--share similarities with the overgrown examples behind the Brush-Everard House, and provide the same evocative aura as the towering bushes surrounding the ruins of Jefferson's Barboursville. In both of these locations, the importance of the plants' associative connections with former owners and memorable past events has been recognized. Additionally, at Carter's Grove, the lively excitement, changing images, and the impressions as one moves along the central path and experiences the constantly shifting scene is irreplaceable.

Some questions are answered and others raised by a 1933 letter from Shurcliff to Archibald McCrea. Reminiscing, Shurcliff says that he realized in 1929 that: "some of the information I had drawn on your plans was not authentic . . . . I enclosed my check to you for $500 which I said would make me feel happier about my charges . . Very shortly after the above events, the depression began with a will and of course you did not need me then."31 It is impossible to pinpoint exactly what 8 inauthentic information is meant, yet it can probably be confirmed that the rumors of curtailment of the projected entrance forecourt and clairvoyee fence imitative of Westover due to lack of funds is true. The same letter reiterates the point that Shurcliff's services were not needed for the present due to the Depression and that he was looking forward to future consultations "when the present hard times come to an end."32

The landscape configuration in the entrance oval has a group of symmetrically arranged American or tree box planted near the house, with the smaller, English variety arranged in random groups on the approach side--all lateral to an axial center vista. Because of Shurcliff's close familiarity with box plants and their growth patterns following his intensive study of southern places after large scale acquisition of box specimens from three states for the Restoration, he surely realized the future results and had reasons for placing the different varieties in the positions which he did. However, if a final landscape plan used for plant disposition existed, it has not been located, and it is hard to say in concrete terms precisely what the Shurcliff/McCrea intentions were. Recalling the fact that the latest prospective scheme shows the landside entrance oval "arranged in scattered formation to look like overgrown planting of great age,"33 it is tempting to surmise that the present configuration approaches the original intent. The conclusion that extensive development plans were possibly curtailed due to the Depression is borne out by Vincent N. Merrill, a former partner in the Shurcliff firm and member of the present-day successor firm in Cambridge, Massachusetts, who writes that "perhaps the final solution was executed on the ground."34

The tree box planted in the landside entrance turnaround, may have been intended to define the forecourt area originally planned for the space immediately in front of the house and behind the clairvoyee fence shown in some of Shurcliff's proposed schemes. Also, they may have been meant to aid in an element of surprise as at Castle Hill, landscape plans of which Shurcliff was drawing up concurrently with his work at Carter's Grove. Correspondence proves that he sent photostats of this plan to the McCreas.35 It is interesting to note in the Castle Hill plan that "very tall hedges of tree box"36 completely obscure the house from the entrance drive approach. Only as the north end of the entrance oval is reached, is there an unobstructed view of the house. The same effect was at one point considered for Carter's Grove. Referring to two of Lee's unbuilt forecourt buildings, Shurcliff, in 1929, wrote to McCrea: "If you have decided definitely to give up the double roadway at Carter's Grove, I hope the loop will be long enough to reveal the very attractive gable ends of the two side 9 buildings."37 There may even be memories of Fairsled, Frederick Law Olmsted, Senior's Brookline home with which Shurcliff must have been familiar. It is described as having an air of mystery at the front entrance with its circular drive around a central hummock which hid both house and grounds.

A further pertinent note concerning the tree box, formerly placed at the corners of the north facade, exists in another Shurcliff letter to McCrea. He says: "I enclose a photograph [Attachment 12] I took the other day of one of the College buildings William and Mary showing the modern way of planting Box at corners. You remember we worried about this kind of planting at Carter's Grove. Although it is very effective it is not after the manner of the old places with the exception of Brandon, where the superintendent told us that the Box had been planted on the approach side more or less in this manner by a local landscape architect."38

Parameters to Shurcliff's design process were definitely set by the requirements of his clients. Archibald McCrea, in a 1928 letter to Shurcliff, asked his ideas on where to place "the 16 large tree box plants, the various clumps and hedge of dwarf box that we now have, and your ideas on the roadway from the end of the cedars to the house."39 The tree box were to be moved from the sunken garden at the McCrea's country home, Brunswick Hall, rear Lawrenceville, Virginia. Another insight into Shurcliff's landscape philosophy, which has bearing on this question, is contained in his published article, "Design of Colonial Places in Virginia," written just before he began work at Carter's Grove. He says: "To combine with an ancient house grounds which do not belong to the period of the edifice is inexcusable. If the owner of the place requires such departures from the old work the blame is only partly his. The Landscape Architect who participates is a party to the fault and very great blame can and should be placed upon him."40

Distinct attributions concerning which decisions were actually made by Shurcliff or the McCreas are hard to make. The camaraderie which existed between Shurcliff and Archibald McCrea, who often accompanied him on surveying trips, is reflected in the following excerpt from a Shurcliff letter to McCrea in 1929. It also indicates that results were frequently a combination of both their efforts. Shurcliff says that the observations which he is making are the "comments of a coworker, not professional advice . . . . To me these notes which we have written back and forth of late and our conversations about old layouts are exceedingly interesting and valuable, and if you hear from me occasionally you will understand it is not with a professional 10 aim but merely to get your own comments in the large field of restoration in which we are both so much interested."41

If radical landscape changes are to be considered at Carter's Grove, it should be remembered that one of the memorable aspects is the long established, exclusive use of one variety of tree--locust--along the landside entrance drive. The plantation and house in particular, have been referred to as "the Grove" since the mid-nineteenth century. When one of these trees was cut following a storm last fall, a count of annual growth rings was made. The trees were evidently planted around the time of the Yorktown Centennial celebration in 1881. It is interesting to note, as a landscape historian recently explained, that commemorative groves were frequently planted to memorialize notable events during the nineteenth century.42 As mentioned before, this singular feature, recognized by Shurcliff, was enthusiastically and positively remarked on in a letter to the McCreas. Recently, Dick Mahone has pointed out the ideal conditions of growing locusts and box in combination. The former are deep rooted, while the latter are shallow. This happy circumstance would not exist with some other tree varieties.

William G. Perry, an early admirer of Carter's Grove and contemporary witness to its transformation, reminisced that "…in came the McCreas and, failing to buy Westover, determined that they would make Carter's Grove look like Westover."43 The fact that the house, as it exists today, was modelled on the Byrd mansion is reflected in the gardens as well as in architectural details. The position of the large box square to the west of the main house is similar in location to the box garden at Westover. Enclosed by box at Carter's Grove, this area was formerly a flower garden some remnants of which still exist. The plot, as developed by the McCreas, was a series of planting beds bisected with grass walks. Growing in the beds were annual and perennial flowers with bulbs. Don Parker describes a row of peonies as particularly memorable and says that, at some point around 1963, the beds were eliminated and put back into grass to reduce maintenance costs. Restoration of this feature could add general interest and a better understanding of early 20th-century, country house life.

The fact that Shurcliff had his first training with the founder of landscape architecture in America, Frederick Law Olmsted, Sr., ties his work philosophically to Olmsted's romantic, naturalistic vision of garden design expressed in Central Park's "Greensward Plan." Also, Shurcliff was involved with Olmsted's innovative work at Biltmore. Of this project, F. L. Olmsted, Jr. writes that many believe it to be "the beginning of an era of great American country houses."44 11 A recent critic of landscape architectures says: "Shurcliff was one of the elder statesmen of the profession . . . The work at Williamsburg is generally regarded as the greatest of his many outstanding accomplishments."45

Also relevant is the Foundation-sponsored study, "History and Interpretation of Carter's Grove" by Gus E. Hamblett, in which, concerning "the beautiful McCrea era planting in the northern vista," he concludes that it "should be retained with its Shurcliff-inspired plantings in the 1920s vision of a brambly garden-like approach. This charming and successful piece of landscape design has matured beautifully and should be preserved intact."46 Under any circumstance, the romantic observations of William G. Perry that Carter's Grove was "a Shangri-La, so quiet, so motionless, so reminiscent of the past. You could hear the corn growing . . "47 seem to be the pleasant, yet thought provoking, atmosphere which should be striven for.

Article 10 of the "Charter of Florence," recently drawn up by the ICOMOS International Committee on Historic Gardens is worth consideration too. It states: "All maintenance, conservation, restoration or reconstruction of an historic garden or part of one must be applied simultaneously to all its constituent features. To differentiate treatments would destroy its unity."48

It would be my recommendation that stabilization of the existing landscape pattern at the landside entrance be carried out, and efforts made to rejuvenate and restore lost elements for a number of reasons. Hosmer's recent publication, Preservation Comes of Age, notes the unique contribution to preservation programs made by Shurcliff and Frederick Law Olmsted, Jr. due to their recognition of this area "as a logical outgrowth of the planning aspects of their profession."49 The opportunity exists to preserve intact one of the few remaining unchanged landscape schemes created by Shurcliff in the Tidewater area, which could be appreciated and studies in combination with his original plans held by the Foundation.

The final decision concerning action to be taken should probably hinge on conclusions reached for interpretation of the exterior. Unless the outside of Carter's Grove is to be returned to its 18th century form--hyphens demolished, roof lowered, dormers removed, etc.--the present landscape, as an integral facet from the rich and eventful McCrea era, should be preserved. The list of statesmen, world leaders, and other public figures visiting during their ownership rivals the record of 18th century notables who also enjoyed its charms. In any case, it would be my recommendation that consideration be given to incorporation and development of the existent garden features with whatever interpretive decision is reached.

G. H. Y.

Carter's Grove

Landscape Features

Footnotes

June 6, 1984

Notes of Arthur A Shurtleff from Surveys

Notes of Arthur A Shurtleff from Surveys

Atch. 2

Castle Hill

Castle Hill

Albemarle Co., Virginia

Country Seat of Prince and Princess Troubetzkoyn

Measured by Arthur A Shurtleff, Feb. 1920

December 18, 1928.

December 18, 1928.

This is a general bird's-eye-view showing the arrangement of box along the front of the house. I have revised this arrangement so it conforms to our conversation of last Friday. This general view shows the new arrangement of grounds with the little buildings moved up nearer the house.

You are familiar with this picture which shows four large box bushes at point indicated on the 20 scale general plan. Between these bushes are the two steps mentioned in my letter. When you actually set out these four plants, I suggest a space of not more than 8 feet between the two central plants between which the two steps are to be set. The two outer box plants should nearly, if not quite, touch the two inner ones and should not be on the straight line but should swing out a little as shown in this picture and as shown on the above mentioned plan.

You are familiar with this picture which shows four large box bushes at point indicated on the 20 scale general plan. Between these bushes are the two steps mentioned in my letter. When you actually set out these four plants, I suggest a space of not more than 8 feet between the two central plants between which the two steps are to be set. The two outer box plants should nearly, if not quite, touch the two inner ones and should not be on the straight line but should swing out a little as shown in this picture and as shown on the above mentioned plan.